In 2022, Hensel Phelps completed the design-build Center for Alzheimer’s and Related Dementias (CARD) Research Facility for the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The project was developed due to an imminent need to support the National Institute of Aging (NIA) and its research, which was previously spread across multiple buildings on the NIH campus in Bethesda, Maryland. A design-build delivery method and a prescribed modular design lead to the achievement of speed to market while fostering enhancements that met NIH’s Design Requirements Manual (DRM).

Design-Build Delivery Method

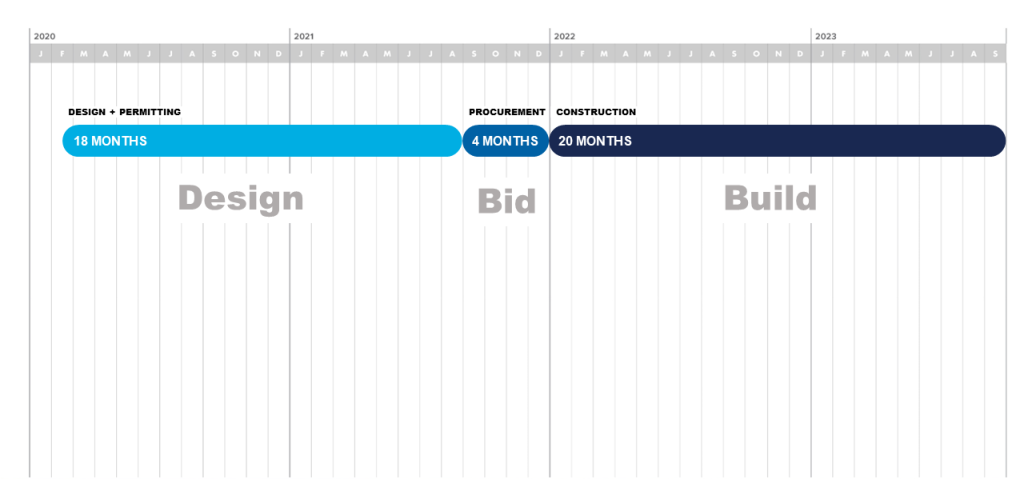

Design-build contracts typically take less time to complete than design-bid-build projects because they eliminate the need for a second procurement process. This reduces errors and omissions in the drawings and allows for concurrent design and construction.

“Because the design team and contractor are under the same umbrella, often working together during the design development stage of the project, design-build projects typically have less risk for the government. One of the significant reasons is because the main point of tension–designer versus contractor –is removed in a design-build contract.”

Mitch Taragin, NIH Contracting Officer on the NIA project

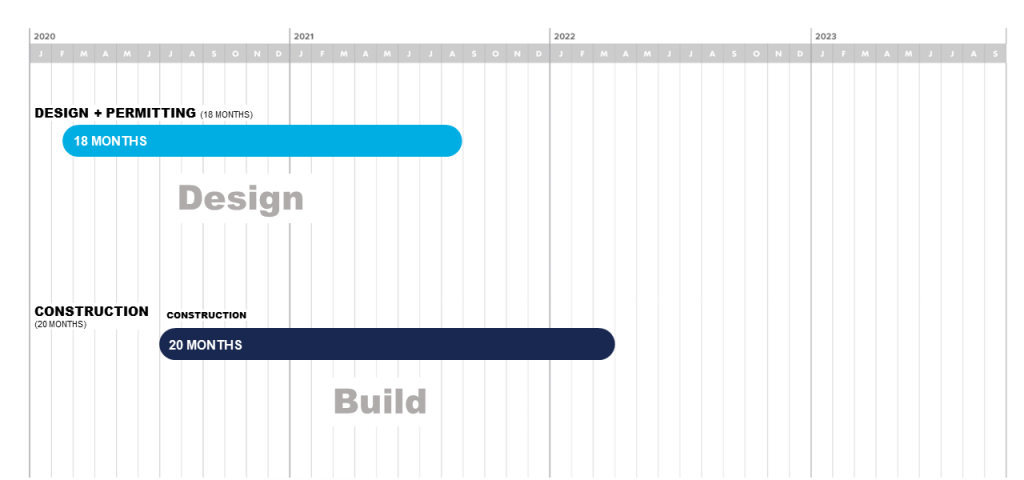

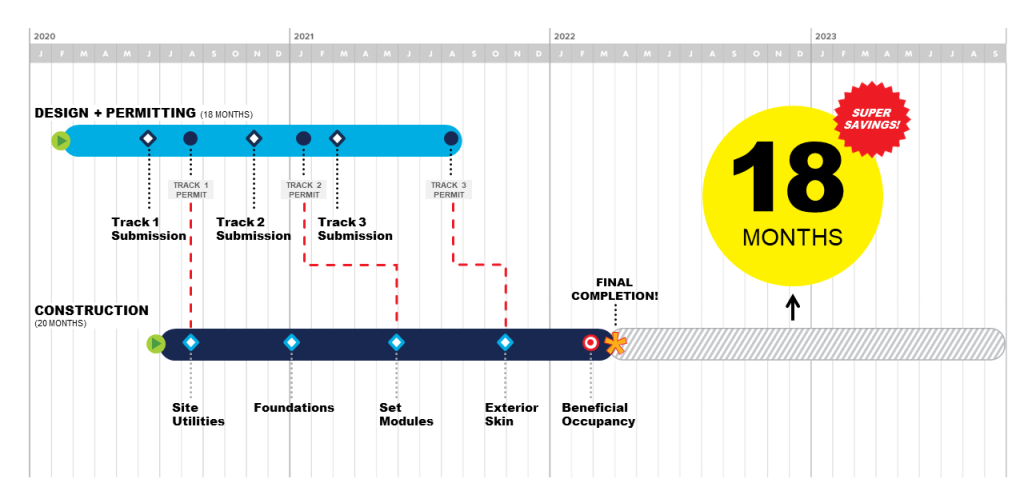

For a project of this size and scope, a traditional design-bid-build procurement schedule would have included 18 months of design, four months of procurement and 20 months of construction. However, by choosing a design-build delivery method, construction shifted to be concurrent with the design.

“In order to do that, we had to be strategic in how we split the design out. We utilized three design packages that all were tied to their requisite permits, which tied to their key construction elements. For example, we tied the site utilities to the foundations, to modules, to the long lead pieces of equipment and to the ultimate build-out and finishes with the building. The overall net effect of doing that was about 18 months of savings. We were able to shift from an overall schedule of 42 months to 24 months, simply by changing the delivery method and being intentional about how we tied design and construction,” explains Matt Frazier, Hensel Phelps’ project manager.

Modular Construction

The building is a single-story modular facility with open-concept labs and offices to reduce cost and construction time and maximize available interior space.

Aspects of the modules that were interdependent to each module were installed off-site at the modular builder’s fabrication facility in Florida. The structural frame of each module was manufactured off-site and wrapped with Tyvek to prevent damage during the trucking process to Maryland. Modular units were sized so that the maximum module dimensions were limited to 11’6″ x 47’, enabling routing through campus without road closures or other traffic-related disruptions.

Hensel Phelps frequently visited the Florida manufacturing plant to provide feedback on the quality of the modules. Through the utilization of StructionSite, the team documented the progress of the modules through 360º photos, allowing any user to select a specific date and view that day’s progress. These processes gave Hensel Phelps and the NIH confidence that the construction of the modules was meeting quality standards.

Collaborative Design

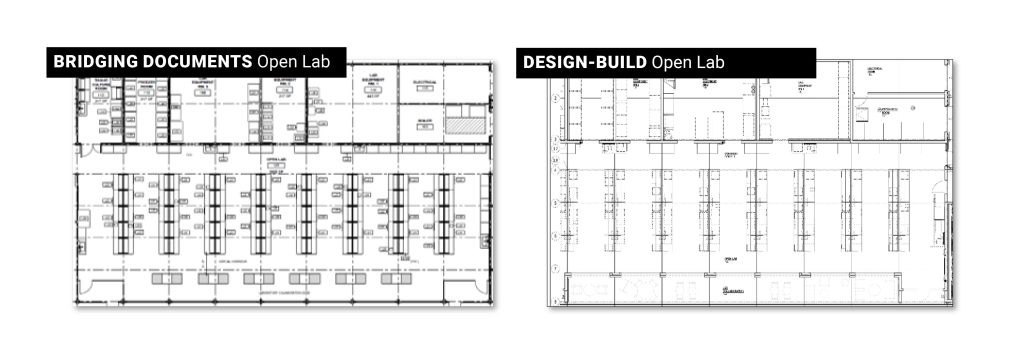

The bridging documents NIH provided during the procurement phase presented opportunities for the design-build team to continue to bring several design enhancements to the project. The design team countered the traditional idea of what a modular building could look like by adjusting the metal panels identified in the bridging documents. The team also collaborated on how to leave NIA’s unique stamp on the building, ultimately creating a sense of arrival in the building lobby through a wall pattern of neurons and a “snake light” to guide the flow of the building.

Similarly, the design team collaborated closely with NIA to advance the program areas in the building. Based on conversations with NIA, the team developed layouts that balanced closed labs and open collaboration spaces to support how the end-user would utilize the space, their research and their culture.

Finally, the team made several structural enhancements to support research flexibility. The bridging documents defined metal framing in the lab and office areas. However, NIA expressed interest in providing a structure that could accommodate a wider range of research over time. The team ultimately made changes to the structure to make the modular units more robust and less prone to vibrations to support sensitive equipment and any future movements in equipment.

Several engineering betterments were also made to the project, including utilizing a single air handler with redundant air tunnels instead of providing two fully redundant and independent air handling units at each location. Recommendations of an electrical commutated motor (ECM) fan array and combining multiple exhaust systems to minimize the number of lab exhaust fans were also implemented. These innovations required a smaller footprint and lower costs while still supporting the needs of NIA.

“With modular construction, you may have to take an engineering in reverse approach. Normally, you do the upfront loads and the larger scale things first, working down to the smaller things. In this case, since the modules were built first and off-site, we started with the electrical distribution design first and worked back to the switch gear.”

Omar Malik, CFR Engineering

While enhancing the bridging design, NIH still required the design-build team to comply with their Design Requirements Manual (DRM). The DRM is the only detailed design requirements and guidance manual of its kind and is utilized on all NIH owned, leased, operated and funded buildings and facilities. Due to the unique nature of the project, the team submitted 20 variance requests, some of which were established in the bridging documents. Many of these variances were also related to the described innovations, while establishing a collaborative environment allowed these variances to push forward.

A facility of the future, the success of the CARD facility comes down to creating a highly collaborative environment through the design-build delivery method.

“This project required a highly collaborative environment. Hensel Phelps really aided in a lot of the communication, and we were able to work through these innovations with the NIH program officer, the end-users and ZGF. Having a design-build team was the only way to allow this to happen,” said Omar Malik with CFR Engineering.